‘According to World Bank’s Energy Progress Report 2025, Nigeria tops the list as the African country with the worst power outages in 2025. The national grid collapse has become so frequent in the last two years with that of September 2025, being the most recent, marking yet another failure in a long history of instability.’

One of the major infrastructural deficits bedeviling the growth of Africa’s manufacturing sector over the years has been the poor access to stable electricity for industrial use. Electricity is the lifeblood of modern economies. It fuels industries, powers businesses, and transforms lives. Yet, across much of Africa, keeping the lights on remains a daily struggle. Factories shut down mid-production, businesses depend on diesel generators, and grapple with rising energy costs that erode competitiveness. In the face of this, Africa’s manufacturing sector, a vital driver of structural transformation and inclusive growth, continues to be constrained by chronic energy shortfalls. The result is stunted productivity, lost investment opportunities, and a manufacturing base that struggles to reach its full potential.

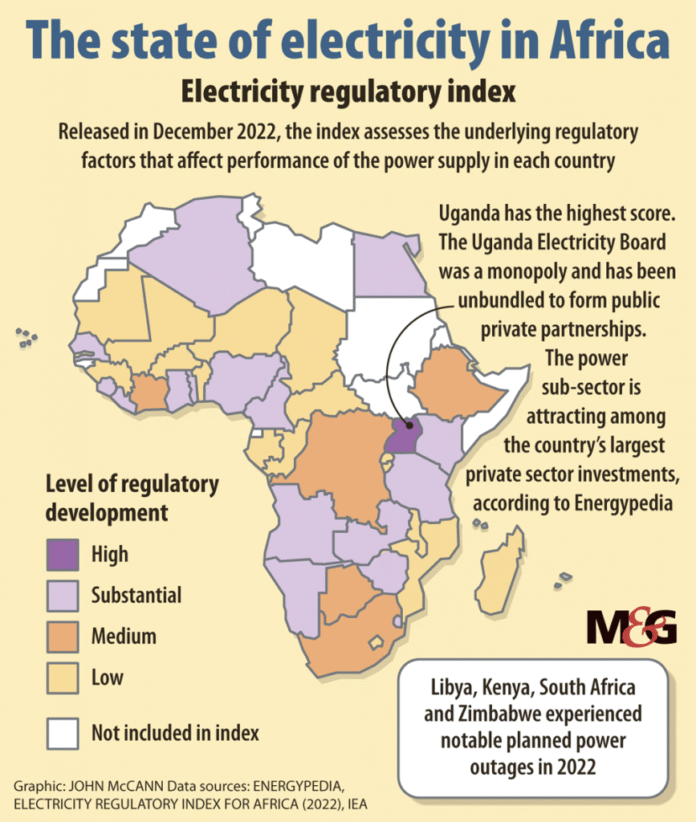

Africa’s energy crisis goes beyond homes without light at night; it is about machines that stand idle during the day, goods that never reach markets, and economies unable to scale because power supply remains unreliable. The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that an average of 56 days of power outages annually, one of the highest rates globally. This chronic deficit not only undermines industrial output but also weakens economic resilience.

In many African nations, population growth continues to outpace new power connections while the pace of electrification remains fragile with records of imports of solar panels from China.

Africa’s Energy Deficit and Its Impact on Industrial Growth

Manufacturing has been one of the hardest-hit sectors from energy scarcity across the continent, forcing factories to either operate below capacity or rely heavily on expensive self-generation, often through diesel or petrol-powered generators, which significantly drive-up production costs.

- Macroeconomic and Sectoral Impact: studies consistently show a significant negative relationship between electricity shortages and economic growth, as frequent power outages directly reduce industrial output and commercial activity.

- Adaptation through production adjustment and input substitution: in response to uncertain electricity supply, firms often adjust their production processes. Some switch from electricity-driven machinery to manual or fuel-based alternatives, while others resort to backup power solutions such as diesel generators or outsource energy-intensive operations. Although these measures help mitigate productivity losses, they rarely offset them completely and often lead to increased operational costs.

- Impact on investment, innovation, and technology adoption: persistent power outages discourage both domestic and foreign investment. Firms become hesitant to expand operations or adopt new technologies that depend on reliable electricity. While larger enterprises may still invest to maintain output levels during supply shocks, their productivity can decline since most modern technologies are power-dependent. This limits industrial modernization and weakens competitiveness.

- Impact on firms’ dynamism: small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the most affected by electricity shortages because they lack the financial capacity to purchase generators or invest in alternative energy solutions. Many are forced to reduce output or shut down entirely, leading to a decline in firm dynamism and job creation. Conversely, improved access to stable electricity has been linked with higher rates of new business formation, stronger firm survival, and overall productivity growth.

Here are a few case studies of how energy deficits have shaped industrial outcomes in some African Countries:

Nigeria: According to World Bank’s Energy Progress Report 2025, Nigeria tops the list as the African country with the worst power outages in 2025. The national grid collapse has become so frequent in the last 2 years with in of September 2025, being the most recent, marking yet another failure in a long history of instability. According to Manufacturers Association of Nigeria, manufacturers in Nigeria spent N1.11tn on alternative energy sources in 2024, indicating a 42.3 per cent rise from the N781.68bn recorded in 2023. The main issues include outdated infrastructure, vandalism, poor maintenance, and an overall lack of investment in generation capacity. Until significant reforms are made, Nigeria’s power crisis will continue to hinder economic and business growth in Nigeria.

Ivory Coast: In 2024, Côte d’Ivoire, one of West Africa’s main electricity exporters, experienced an unexpected energy crisis. Unplanned shutdowns at major power plants disrupted production in key sectors like cocoa processing and mining, causing losses estimated at $8 million. Although the country boasts one of the region’s most developed power systems, inadequate maintenance and an overstretched grid have exposed vulnerabilities that threaten its long-term energy stability.

Zambia & Zimbabwe: Zambia and Zimbabwe are grappling with a shared energy crisis caused by severe drought and regional grid instability. The Kariba Dam, which supplies most of their electricity, has seen record-low water levels, drastically cutting hydroelectric output. As a result, Zambia endures up to 12 hours of daily load shedding, while Zimbabwe faces outages of about 10 hours. These prolonged blackouts have crippled industries, disrupted mining and manufacturing operations, and raised production costs as companies turn to costly diesel generators to stay afloat. Small businesses, in particular, have been hit hard, with many reducing operating hours or closing temporarily. The situation remains critical, with no immediate relief in sight, threatening both economic stability and investor confidence in the two countries.

Burundi: Burundi is currently facing an escalating energy crisis, with power cuts now a daily reality across the country. A major contributor to this challenge is the plastic waste buildup at the Ruzizi hydropower plant, which has significantly reduced electricity generation capacity. Compounding the problem, ongoing fuel shortages have limited the availability of alternative energy sources, leaving industries and households vulnerable.

Tanzania: In late 2024 and early 2025, Tanzania suffered major power disruptions following Cyclone Dikeledi, which damaged key infrastructure and exposed weaknesses in the national grid. Poor maintenance and fallen trees on power lines worsened the crisis, causing widespread blackouts. Businesses faced equipment damage, production losses, and increased operating costs, while small enterprises were forced to scale down, highlighting the country’s vulnerability to infrastructure and climate-related challenges.

Ghana: Ghana, once a model of energy stability, is again battling frequent power outages caused by gas supply constraints, rising demand, and regulatory bottlenecks. The resulting blackouts have cost the economy an estimated $680 million annually, crippling productivity and increasing operational costs for industries. Businesses have been forced to rely heavily on expensive diesel generators, while the sector’s growing debt burden threatens to worsen the crisis and undermine long-term energy reliability.

Benin: Benin continues to experience prolonged power outages, especially in major commercial zones. Ongoing network upgrades have been undermined by transformer theft and vandalism. Businesses report losing about 9.4% of annual sales due to unreliable electricity. Although the government is investing in renewable energy, persistent grid instability remains a major drag on economic performance.

The Cost Implication

Backup generation, often the main alternative to grid electricity, remains prohibitively expensive for African industries. According to a World Bank study, factories across the continent spend around $0.47 per kWh on self-generated power, nearly three times higher than the grid tariff in countries like Nigeria and Uganda. Unsurprisingly, 70–80% of firms in nations such as Nigeria and Ghana rely on diesel generators. In Ghana, where firms lose an average of 15–16% of annual sales to power outages, more than half operate their own generators. These high backup costs reduce profit margins and push up product prices.

In effect, unreliable electricity functions as a hidden tax on African manufacturing. Even brief blackouts have large cumulative effects, for instance, the Kenya Association of Manufacturers estimated in 2023 that grid failures cost the economy about $2 million daily in lost output. Regionally, such inefficiencies erode GDP.

For energy-intensive sectors like cement, steel, and chemicals, the strain is far greater. Erratic power supply forces them to overspend on backup generation or cut production altogether. Ultimately, the burden of Africa’s energy crisis falls squarely on manufacturers through lost productivity, high operating costs, and uncertain power availability.

Power Outage and Back-Up Cost to Firms in Selected African Countries

Source: World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

Pathways Forward

It is no doubt that the challenges facing African industries resulting from energy deficit are daunting, the situation creates an opportunity for African leaders to respond with policy and investment initiatives aimed at transforming its energy-industrial nexus. Governments and partners must align energy reforms with industrial policy to catalyze growth. Key priorities should include:

- Infrastructure Expansion and Grid Strengthening: African countries must aggressively up-scale capacity growth in renewables and transmission. World Bank and AfDB estimates suggest Africa needs tens of gigawatts of new generation (mostly renewable) by 2030. Crucially, new investment in distribution is required so factories in provinces can actually receive power.

- Market Reforms and Pricing:

Transparent, cost-reflective tariffs are essential for utility viability. At the same time, regulators should enforce service-quality standards so that higher tariffs actually buy reliability. For manufacturers, this means they should see tangible improvement for any rate hikes. Similar measures, such as fast-track permits as seen in South Africa and Nigeria to entice private off-grid solutions should be encouraged across other African countries.

- Industrial Energy Policy Integration: Energy policy cannot be siloed away from industry strategy. Ministries of trade and industry must coordinate with power planners. African Union Agenda 2063 and national industrialization masterplans often mention infrastructure, but many lack detailed electricity targets. This must change: as AfDB and UNIDO stress, energy access is a binding constraint on industrial competitiveness.

- Private Sector Engagement and Financing: Governments should mobilize private capital for power projects that serve industry. In practice, this means co-financing solar parks, expanding credit facilities for factory micro-grids, and using guarantees to lower borrowing costs for utilities. For manufacturers, contract structures like long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) or lease-to-own solar schemes should be encouraged.

- Renewable and Decentralized Solutions: Africa must jump-start the green transition while meeting demand. Continued rollout of solar and wind farms is vital: Africa has abundant solar irradiation, and costs are now among the world’s lowest. Distributed solutions, rooftop solar on factories, hybrid “grid-plus-storage” plants should be mainstreamed. Governments should support initiatives such as this by simplifying grid interconnection rules and guaranteeing wheeling access for independent generators.

In conclusion, Africa leaders must be intentional about accelerating the continent’s renewables, expanding grids and off-grid solutions, and aligning energy markets with industrial goals to unlock Africa’s manufacturing potential. The continent must double down on integrated energy-industrial strategies by scaling up reliable power is the single most important step to ensure Africa’s factories and workers can compete and thrive.

Source:PAMA News Bulletin (Pan-African Manufactures Association)