‘Estimates range widely for what it would cost to bring back the industry. One reasonable guess is $20 billion to boost Venezuela’s output to 1.5 million barrels a day from the 870,000 barrels it produced in November. To get back to the 3.4 million barrels a day of peak production at the end of the 1990s could cost $100 billion or even more, including new facilities, infrastructure and environmental remediation.’

Daniel Yergin

“No one was paying any attention to Venezuelan oil two weeks ago,” a longtime oilman said to me the other day, “but now everyone is.” Donald Trump made that happen. Following the dramatic seizure of dictator Nicolás Maduro by American forces on Jan. 3, the president declared that the U.S. would take control of the country’s oil industry, with Venezuela turning over 30 to 50 million barrels for the U.S. to sell, the proceeds being used “to benefit the people of Venezuela and the United States!”

But that’s just the beginning. Trump has made clear that he wants U.S. oil companies to return to Venezuela in a big way.

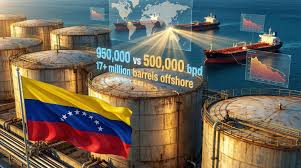

There’s certainly plenty of oil to be produced there. Venezuela holds the largest reserves in the world, more than Saudi Arabia and the U.S., and for decades was one of the stars of the oil world. But recent years have brought a crushing descent. Venezuela has been producing well under a million barrels a day—less than North Dakota—and accounts for less than 1% of world oil production.

Estimates range widely for what it would cost to bring back the industry. One reasonable guess is $20 billion to boost Venezuela’s output to 1.5 million barrels a day from the 870,000 barrels it produced in November. To get back to the 3.4 million barrels a day of peak production at the end of the 1990s could cost $100 billion or even more, including new facilities, infrastructure and environmental remediation.

But what will it take to persuade companies to make such big bets on Venezuela again? The country’s state-owned oil company, devastated by years of corruption and political turbulence, doesn’t have the money or technology for a recovery, let alone a massive upgrade. The international oil companies who do will want to be confident about security, regulation and the legal foundations of their investment, given that Venezuelans across the spectrum—including most of the 70% of the public that voted against Maduro in the last election—believe the country’s oil resources belong to the nation and are essential to the recovery of their battered economy. Any real plan for reviving Venezuela’s oil industry has to reckon with the political legacy of the country’s long, turbulent history with its petro riches.

From ‘mirage’ to oil boom

The hunt for oil in Venezuela began before World War I in unmapped jungles whose hazards included giant mosquitoes, malaria and hostile native tribes. One driller, sitting on the porch of a mess hall, was killed by an arrow fired from the nearby jungle. The results of the hunt were so disappointing that in 1922 an American geologist dismissed the country’s petroleum prospects as a “mirage.”

But as has so often happened in the history of oil, when just about everyone is about to give up on a new geography, a discovery proves them wrong. Later that same year, Royal Dutch Shell, the Anglo-Dutch company, found an oil field so huge that the initial well flowed at 100,000 barrels a day. That set off an oil rush that drew in more than a hundred U.S. and British groups. An oil boom engulfed the country. Within seven years, Venezuela had gone from nothing to become the second-largest oil producing country in the world, behind only the U.S.

Oil became the foundation of the economy, generating 90% of export earnings. No one benefited from the boom more than the country’s dictator, the avaricious and brutal General Juan Vicente Gomez, and his family. They showed remarkable business acuity in selling the rights to new oil concessions to companies eager to get into the game.

By the late 1940s, more than a decade after the death of Gomez, a reformist group won control of the government and demanded a new arrangement with the oil companies. In a deal partly brokered by the U.S. government, oil proceeds were divided on a “50/50 principle,” with companies paying taxes and royalties to the government equal to half their net profits on the oil.

The new terms, plus expanding production, led to a sixfold increase in government revenues and contributed substantially to the country’s impressive postwar economic development. There could be no doubt that Venezuela was now well established as a petrostate.

But the 50/50 deal didn’t last long. Nationalism would change the balance, with Venezuela passing a law in 1958 to increase its share to about 60%. In 1959 and 1960, international oil companies, facing a surge of new supplies from the Soviet Union, cut prices. That in turn reduced the income of the other oil-exporting countries. In response, an infuriated Venezuela took the lead with Saudi Arabia in establishing a new organization called the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries—better known as OPEC—to defend their interests.

OPEC and rising demand

OPEC’s founding was a sign of what was to come. As markets tightened in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the face of rising demand, a wave of nationalism swept over oil-producing countries. Venezuela nationalized the companies’ positions, not through confrontation, as in some other countries, but by a process of tough negotiation. Longstanding oil concessions were fashioned into four government-owned operating companies, staffed by Venezuelan nationals who had been trained and worked in the international companies. The new state companies kept their links to the former owners in order to maintain technical skills and to make sure the oil could get to market.

The four operating companies were under the national oil company, PdVSA, which existed both for coordination and, importantly, to provide a buffer between politicians and the operating companies, to guard them against political interference and to reduce corruption. When I visited Caracas in the 1990s, meeting with PdVSA and its subsidiaries was like meeting with any other professionally run international company.

But at that moment the Venezuelan economy was already in deep trouble. Population had doubled in just two decades, per capita incomes had fallen, and inflation was high. The only obvious way to bolster the economy quickly was to increase oil earnings, and the only way to do that was by substantially boosting output. But PdVSA could not do it alone. It had neither the investment capital nor the technology.

To be continued next week Thursday.